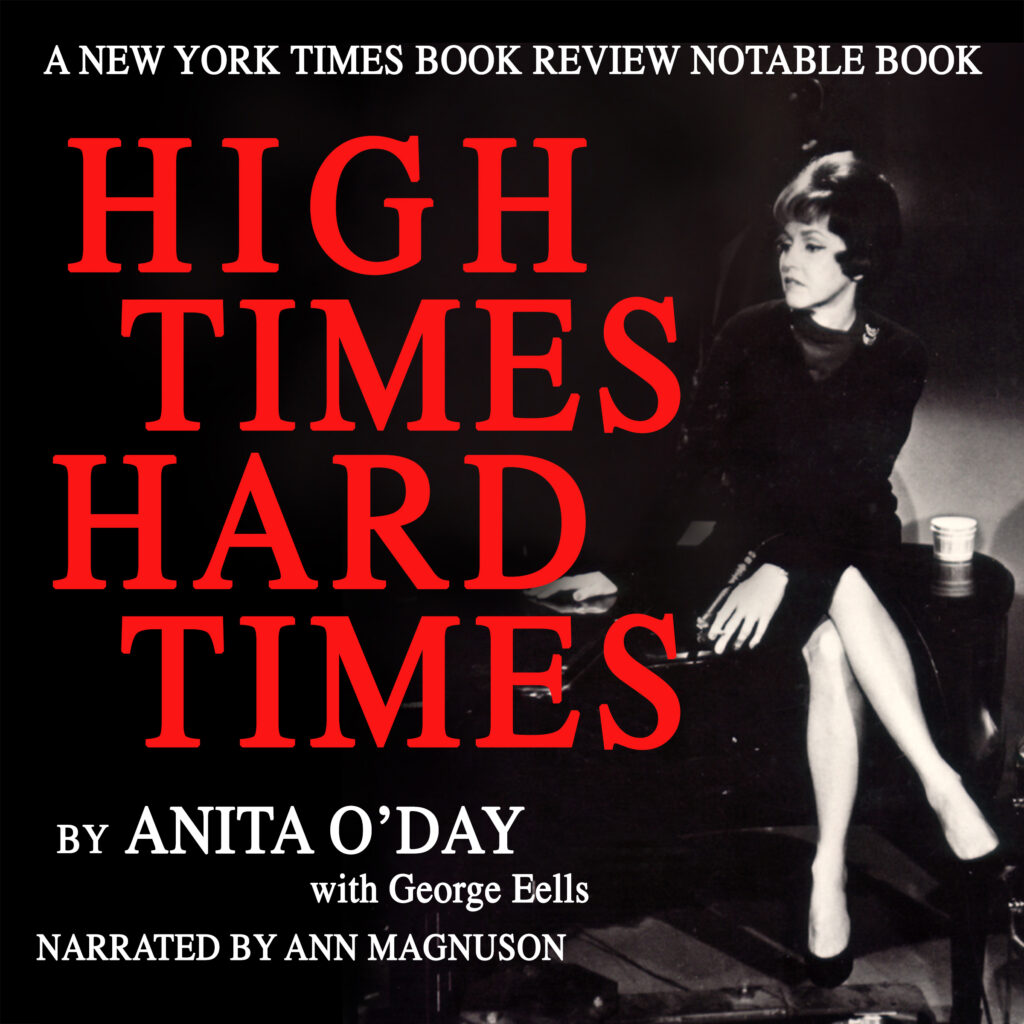

High Times Hard Times

Autobiography

High Times Hard Times Audiobook Available NOW!

High Times Hard Times Audiobook Available NOW!

“…in the tradition of the best jazz autobiographies…a fascinating travelogue through the jazz world, filled with vivid images of Gene Krupa, Stan Kenton, Roy Eldridge and Billie Holiday…Her prose is as hip as her music.” – The New York Times Book Review

A valuable, revealing, and read-at-a-gulp account of a premier American artist and the punishing winds that shaped her life and her craft. ― The San Francisco Chronicle

A remarkably truthful book ― The Chicago Tribune

There’s a pithy edge to Ms. Day’s narrative, a certain comical ‘give ’em hell’ combativeness that shines through the book’s many dark moments. ― Detroit News

The record of [the] early years is like the story of the music itself; rich, exciting, innovative; featuring the primitive beauty of the twenties when one foot was still in showbiz; the thirties with hip sophistication and hard swinging for hard times; the explosive forties of pre-war big band bashes and post-war bop; and then the fifties, going off in a hundred directions with a needle in the arm…it is the best jazz autobiography I’ve ever read. — Jim Christy ― Globe and Mail

This no-holds-barred account of Anita’s career ups and downs, drug fables, romantic interludes, and musical tales is fascinating reading. ― LA Weekly

Purchase via Amazon

Excerpt from High Times Hard Times

Chapter 1 ‘EXCESS BAGGAGE’

Getting pregnant while she was single was something I don’t think my mother ever got over. That was really a heavy situation in 1919. Girls killed themselves, became prostitutes or got married and carried the guilt with them all their lives. Mom took the last route.

Mom’s unmarried name was Gladys Gill and early pictures show an outdoorsy girl with devilish eyes and her own kind of prettiness. There she is, crouched in the crotch of a tree holding a rifle and the squirrel she’s just bagged. Or, on another occasion, she’s astride a horse, wearing a jockey suit at a time when most women didn’t wear pants. But by the time I became old enough to remember her, she was solemn, if not downright grim.

Mom and Dad were both from Kansas City, Missouri. Mom had a half-sister, Aunt Belle, whom she was closer to than anyone else in the world. Aunt Belle stepped in and took care of her after their mother died, until Mom was old enough to go to work in the box factory. That’s where she met Dad, whose name was James Colton.

Dad was an only child, a happy cat, a personality kid. He was tall, slim, with dimples and a delicate bone structure, all of which I inherited. He was also handsome, sandy-haired, and he drank a lot. He was a real ladies’ man and wound up having ten marriages and nine wives before he was fifty.

He must have had a great line to get Mom to “go all the way,” as they said back then. Anyway, he did what nice guys did when Mom told him she was pregnant. He married her. aqBut I wanted her approval too, and I worked for it. Maybe that’s why I ended up with the worst of both of them. No, no, that’s a joke, folks.

Music was really our only bond. Mom kept the radio going constantly. A new song would appear and we’d have something to get excited about. Not that we agreed. She was crazy about “Beyond the Blue Horizon” and “Cryin’ for the Carolines” while I tried to get her interested in “Exactly Like You” and “On the Sunny Side of the Street,” which she thought were just a lot of noise.

She tried not to miss Horace Heidt and His Musical Knights or Shep Fields and His Rippling Rhythm. But it ruined her day if she missed Wayne King’s broadcast, especially a new hit he had around 1932 called “The Waltz You Saved for Me.” She kept the radio on after I went to bed, so I used to go to sleep to the strains of the Lady Esther Serenade, as Wayne King’s program was called. That was certainly going-to-sleep music. Nytol!

Seriously, I loved listening because the Wayne King Orchestra often played just down the street at the “beautiful Aragon Ballroom” which was located on Lawrence ,not too far from us.

Those memories may not sound very intimate to you, but they were about as close as Mom and I got. I think that for a long time after she and Dad split up, her emotions were frozen. I don’t remember her ever kissing me or even smoothing my hair

affectionately. I can understand all that now, but at the time I kept trying to figure out what I’d done that made me so unlovable.

I suppose the Depression worried her, too—the possibility of losing her job—but it didn’t really change anything much for us. Where we were it was always Depression times. Mom gave me fifteen cents for lunch. During the worst times, maybe she cut that to a dime, but a dime went a long way back then. I didn’t suffer. I still wore the same kind of gingham wash dresses. We’d never had any money. So how could we lose what we’d never had?

But when I was around twelve years old, all the kids began getting bicycles. One of my friends let me try hers and after a couple of failures, I found the secret of it. Nobody had to hold the bicycle or help me keep my balance, I was a natural. I rode along feeling the wind against my face and running through my hair and I thought this is really neat. I began picturing myself whizzing along the streets waving at my friends, dazzling them with my fancy circles, figure eights and the classic “Look, Ma, no hands.”

I knew what Mom was going to say if I broached the subject to her. She’d tell me I had no more sense about the value of money than Dad, that she worked long and hard to keep a roof over our heads and food on the table, then she’d go on about how hard it was to keep me in dresses and shoes and the upshot would be that there just wasn’t enough bread for something silly like a bicycle.

I knew she’d parade out all those clichés, but I couldn’t get that red bicycle with silver trim out of my mind. I really believed that if I could have one that was all I’d ever want in this world. So finally one night I blurted out my request. And Mom responded as if I’d written out the speech for her.

I didn’t cry or beg. I just looked at her defiantly and said the thing I knew would bug her most: “Okay, I’ll ask Dad.”

“You just do that,” she told me. “See which comes first, his whiskey or you.”

That night I couldn’t sleep thinking about the red and silver bicycle. I kept seeing myself whizzing along, like wow! causing people to turn in wonder at this vision of speed and grace.

I had to have a bike so a couple of days later I stole one. It didn’t have any silver trim, but it was a boy’s red bicycle. I saw this kid ride up, get off and lean it against the wall outside the corner drugstore. I stood there staring at it, my insides feeling like jelly. I looked around. There was nobody in sight so I hopped on and pedaled away as fast as my legs would take me.

I knew I had to paint it. It hurt me to do it, but I’d already learned that in this world you can’t have everything. If I went riding around on the bike with its original red paint job, the kid would spot it and recognize it. So I took it home and painted it black. I hated black; but it covers red better than any other color. When I’d finished, I looked at it and thought, Yeh! Now I got my own bike! and I put it away to dry.

Mom never even noticed or, if she did, she must have thought some friend was letting me borrow it.

About the third or fourth day, I was really getting expert at wheeling it around. I went to the park and was riding around showing off a little, hoping some of my friends would see me and tell everyone what a great rider Colton was. Instead, the kid who owned the bike saw me. I wanted to zoom off, but I figured then he’d know what I’d done so I pretended not to notice him and hoped the black paint would fool him.

No such luck. He came up and wanted to know where I’d got my bicycle. “Aw, I had it a long time.” “What if I told you it’s mine?” “You’re goofy. Your bike’s red.” “How’d you know that?! It is my bike! You-” I sped off, but he found out my name and where I lived from the other kids. That night he brought his father over to talk to Mom. They had the serial number to identify the bike and I found out right then you have to do more than slap a little black paint on something to get away with stealing it.

It broke my heart to part with that bike and I was embarrassed at being caught, but what humiliated me most of all was to hear Mom apologizing and telling these strangers she didn’t know what she was going to do with me; I was becoming just like Dad.

With Mom, punishment never fit the crime. It was always the same whether she caught me in a fib or stealing a bicycle. She knew that the high point of the day for Uptown kids came after our evening meal at 5:30 P·M· By 6:00, we’d gather and hang out around the corner. When it got dark, we’d go home. Big deal! But I had to be sick or out of the city to miss being there. After I stole the bike, Mom said, “No going to the corner tonight. “

“Aw-”

“Not even off the front porch for a week. You understand? Once you’re home from school, you’re grounded. You’re going to learn right from wrong beginning here and now!”

I felt as if I were in prison. Mom would barely speak to me. For a while I just sat. Then I remembered that summers when I was visiting Grandma and she took me to Sunday school, the teacher said we were to pray to Jesus for guidance when we were bad. I prayed for Him to show me the way and tacked on a request that He would find a way for Mom to get me a bicycle.

I must have appeared very forlorn or, I thought, maybe Jesus had spoken to Mom about my prayers, because not long after, her heart softened. She took me to Sears and picked out a red-and-chrome girl’s bicycle. She paid twenty-five cents down and twenty-five cents a week. It was all she could afford.

It was probably the biggest thrill I’d had up to then. I not only got the bicycle, I looked on it as proof Mom did love me even if she didn’t make a big thing about it.

It wasn’t until later it occurred to me maybe Mom was just being practical. I’d almost finished at Stewart and it was going to be too far for me to walk to Senn Jr. High. Certainly the Sears’ weekly payment was less than a week’s bus fare· Was that why she’d bought me the bike?

I was never going to impress anybody with my grades, but I shone in gym and music, especially during the Friday afternoon homeroom programs. These were impromptu, volunteer happenings. There were tap and acrobatic dancers, a dramatic reader, a few singers (a boy with a high tenor voice was very popular), chalk talks—anything any of us could do or dream up. I’d usually volunteer near the end. My specialty was novelty songs with audience participation. One I remember was “All the King’s Horses·” It went:

The King’s horses and the King’s men,

They march down the street

And they march back again.

Up front, I’d have my classmates primed to ask, “Who?” And I’d sing:

The King’s horses and the King’s men.

I’d heard that number on the South Side one night when George Beiber and I competed in one of the Lindy Hop contests they were holding around the city. George was a big, fat, twenty-five-year-old who was really light on his feet. He had perfect coordination, a great sense of rhythm and such acrobatic skill he could make it look as if I were flipping him over my head. Mom trusted him because when he promised to have me home by midnight he always did.

People ask me when I first smoked grass. Well, I smoked it before it became illegal in 1933, although it really wasn’t legal for me to smoke anything then. But before going in to our dance, George and I would share what we called a reefer. It was no big deal when I was twelve or thirteen. If you lived in the Uptown district, you could buy a joint at the corner store, if not nearer. I never read the newspapers so I didn’t know when pot was outlawed and beer became legal. One night I asked George for a hit on a joint and I thought he was going to flip out. “Do you want to get us arrested?” he hissed. Then he told me what had come down. It didn’t make sense. One day weed had been harmless, booze outlawed; the next, alcohol was in and weed led to “Jiving death.” They didn’t fool me. I kept on using it, but I was just a little more cautious.

George and I usually won in our category. In fact, we became sort of unofficial Lindy Hop champions around Chicago at the time. First prize in most contests was ten bucks. I’d let George keep seven since he was so much older, and I’d take three home to Mom. George couldn’t understand that. I’m not sure I did myself. I told him I pitied her and didn’t want to be a burden. But maybe giving her that money was my childish attempt to prove she was wrong. I wasn’t like my father who hardly ever gave us a penny. I was a giving person like she was.

George wasn’t my boyfriend. We were both natural dancers and made an eye-catching team. I did get interested in a boy named Steve about this time. He was the type I almost always went for in later years: curly blond hair, blue eyes with a devilish glint, and a good physique. He was my first big crush. Years later when I was appearing in Las Vegas, he came by to see me. He owned a little circus. Time seemed not to have touched him. After he left, I wondered what my life would have been if I’d stayed in school, we’d kept going together and maybe married. Well, we’ll never know, will we?

With the arrival of spring I was already feeling restless when my advisor called me for a conference. He pointed out my grade average had dropped so that Commercial Geography was the only subject I could hope to pass. I promised to apply myself more, but all the way home I kept thinking how hard Mom worked and what a disappointment my report card would eventually be to her. I decided to give her a break by forgetting about school and visiting my grandparents. It wasn’t exactly running away. I was just moving up the date for my regular summer visit and saving Mom bus or train fare.

The next morning, after she left for work, I threw a few things into a handkerchief—I think I’d seen too many B movies—and went to the intersection near our house where I asked some sharp-looking dude the way to Kansas City. He told me which city bus to take to reach the edge of town and which highway led to K.C. I thought, “Well, now there you are! How hard can it be?” What I didn’t realize was that the trip was around five hundred miles and would take four nights and five days.

One thing to remember: This was Depression time. Some people felt lucky to be living in piano crates. Another homeless child more or less wasn’t anything for anyone to get excited about. There were lots of them roaming around the country. People were too busy keeping a roof over their heads to bother a mature-looking twelve-year-old who seemed to know what she was doing.

Lots of truck drivers stopped to give me a lift. Most of them were kindly family men; some of them were scum. One thing I got hip to very quickly was not to get in with any driver whose rig sported a “No Riders” sign. That guy invariably had other ideas about the kind of ride I needed. The worst of these picked me up on my second night out. I was tired and chilly and the warmth of the heater quickly made me drowsy. I was half asleep when I realized the truck must have stopped. You know, like I didn’t feel the vibrations anymore. But I did feel the guy was beginning to mess with me, whispering, “Wake up, honey.”

“Are we in Kansas City?” I mumbled.

“No, baby. On the side of the road. Just you ‘n’ me.”

Him and me! I felt my slacks being unbuttoned. Suddenly I was wide awake. All I knew about sex then was what I’d heard from the kids on the corner. Mom and I would have been embarrassed to talk about anything so intimate. But instinct took over. I let him have a knee where it would hurt most, wrenched open the door, jumped out and ran toward a bright area down the highway. The lights came from a roadside cafe. Nothing fancy, a place where truckers stopped.

I sidled in and got up nerve enough to approach the counterman.

“Can I sit here until dawn?”

“How old?”

“Sixteen,” I said, thrusting my front to show how I was starting to bloom up there.

“What’re ya doin’ here?”

“I hitched a ride with a trucker. He’s very nasty and I don’t want to be where he can get me.”

Upset as I was, I didn’t feel like crying, but I managed to squeeze out a tear or two for effect.

The counterman must have realized I was really only thirteen or fourteen, and I guess he pitied another loser because he took the trouble of lining up a ride with a nice family man who also happened to be a trucker. This man drove me into the downtown area of Kansas City and helped me look up Grandpa’s address in the telephone book. When I finally got to the house, there was no one home. I sat on the steps until the lady next door recognized me and wanted to know what I was doing there.

“Waiting for Grandma.”

“Annie’s at church on the corner,” she said.

I might have known. We always spent a lot of time at that church during my visits. What I learned there supplied me with some much-needed strength to see me through the rough hours of my addiction later.

I’d enjoyed my first night’s sleep at Grandma’s when Uncle Vance showed up looking for me. Uncle Vance was a traveling salesman for a pots-and-pans organization, but he was a pretty straight cat. He explained that Mom had been frantic when she called him. Why she hadn’t called Grandma I have no idea, but hearing that she really was concerned about my welfare made me glow inside.

Maybe I wasn’t just excess baggage after all.

After Uncle Vance pressed a bag of goodies into my hands and put me on the train headed for Chicago, I spent most of the trip dreaming of all the things Mom and I would say to one another when I got back. If they sounded suspiciously like soap opera, maybe that was because those radio dramas and an occasional movie were the only places I ever heard people talk about love and loneliness and the need for one another. Nobody at our house expressed feelings. Anyway, the emotional bath that I imagined would take place when Mom and I saw one another again would have made Mother Monahan, that sentimental old busybody on “Painted Dreams,” seem like a cynic.

As the train pulled into the station, my heart was pounding and I could hardly wait for the doors to slide open. I rushed out of the railroad coach and ran along the platform, ready to hurl myself into Mom’s arms. As I took the steps two at a time, I could see Mom standing there by the train gate, just as Uncle Vance had said she’d be. My stomach knotted as I looked at her. She wasn’t smiling; she didn’t even look as if she was glad to see me. I started taking the steps one at a time. I guess I’d always really been hip to the fact that she’d never tell me any of the kind of stuff I’d imagined on the trip. But any sign she felt something toward me would have been welcome, from a kiss on the cheek to a slap.

Of course, that wasn’t Mom’s way. I can still remember her exact words as I climbed the steps: “Hurry up, Anita. For heaven’s sake, dinner’s going to be late enough as it is.”

Excerpt from High Times Hard Times

by Anita O’Day

Courtesy of Limelight Editions,

an Imprint of Hal Leonard Corporation

ISBN 978-0-87910-118-3

To order call 1-800-524-4425

or visit your online or local bookstore