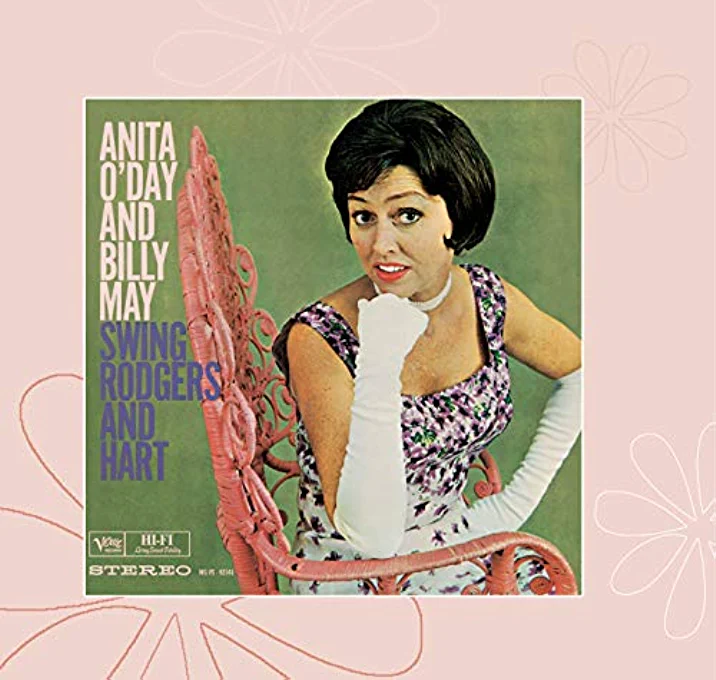

Anita O’Day Swings Rodgers and Hart with Billy May

JOHNNY ONE NOTE (Babes in Arms, 1937)

LITTLE GIRL BLUE (Jumbo, 1935)

FALLING IN LOVE WITH LOVE (The Boys from Syracuse, 1938)

BEWITCHED (Pol Joey, 1940)

I COULD WRITE A BOOK (Pal Joey), 1940)

HAVE YOU MET MISS JONES? (I’d Rather Be Right, 1937)

LOVER (Love Me Tonight, 1932)

IT NEVER ENTERED MY MIND (Higher and Higher, 1940)

TEN CENTS A DANCE (Simple Simon, 1930)

I’VE GOT FIVE DOLLARS (America’s Sweetheart, 1931)

TO KEEP MY LOVE ALIVE (A Connecticut Yankee, 1943)

SPRING IS HERE-( I Married an Angel, 1938)

From Ballhaus, bohe de nuit, and the dark clubs across America still comes occasionally the smoky voice of the jazz chanteuse. Decades ago we heard its cousin course through Berlin, the residue of Whiskylachen and a world between wars. In those days it specialized in lamentation and a slowed tempo, putting its material into a, Weltsprache, a language whose meaning everyone can feel even when he cannot understand.

The tradition continues, but memorably only in the singular voice. Of recent years we have listened to it in Anita O’Day, with her personalized inflections. We hear her other qualities as well: the up-beat tempo, exciting phrasing, calculated dissonances, and personal point-of-view – all of these the now-essential components of her style. But more and more we appreciate Leonard Feather’s perceptive judgment of her, a judgment made many years ago: a Giant of jazz. And just as Lotte Lenya in the Twenties accelerated interest with her adiaphanous voice, so ever since 1941 when Anita joined Gene Krupa’s band and popularized an American version of the same appeal has she been among our most important jazz vocalists. The evidence of her significance lies not only in the large numbers of her audience but in the success of June Christy and Chris Conner who came after her.

Timbre alone cannot guarantee a listener’s interest in familiar material, however. And when Anita O’Day joins with Billy May to get off a dozen Rodgers and Hart standards, both singer and arranger-conductor rely on their ingenuity to show -what can be done with show music. They set themselves a similar’ assignment sometime back when they cut a Cole Porter album and immediately revived interest in several seemingly too-well-known ballads. Now they have used the same proficiency on twelve songs which have be -come part of our national cultural legacy.

“Larry and I worked together for over twenty-four years, from the time I was sixteen and he was twenty-three until his death in 1943 when I was forty and he forty-seven,” wrote Richard Rodgers. “This was possibly the oldest partnership -in the history, of the theatre the first Rodgers and Hart collaboration to be on Broadway was “Any Old Place with You,” interpolated into 1919’s A Lonely Romeo; among their last songs was this album’s “To Keep My Love Alive,” supplied for the 1943 revival of A Connecticut Yankee. In those intervening years of the Twenties, the Depression Thirties, and a world adrift toward war, This team provided our musical theatre with an array of jaunty tunes and glittering lyrics _. Their first hit, according to Rodgers, was Manhattan”; and though ‘ the books for their shows remembered Shakespeare (The Boys from Syracuse), Twain (A Connecticut Yankee) and even Chicago (Pal Joey), in a number of minds the lyricist and the composer linger as the writers particularly, of New York. Perhaps it was their sophisticated allusions, the pulsating Rodgers tempo and the witty, heartfelt rhymes. “In the face of the pin-wheel brilliance of some of Larry’s work, one is inclined to forget, the deeper phases of his writing.” The remark reflected Rodger’s instinctive awareness of his partner’s early flippancy and his later compassion. Certainly Hart’s ability to ‘ turn his humorous allusions and compilation of tastes into an effective delineation of character developed as he wrote on. It reached a peak in this album’s .’It Never Entered My Mind,” certainly one of the finest songs the team produced.

The twelve songs chosen by Anita and Billy May for this albumappeared in shows presentedin the last dozen years of Rodgers and Hart”s collaborative career. Chronologically they rangefrom “Ten Cents a Dance” (that Ballhaus blues of 1930, with its mordant patter lightly etching adeeper plight, a number seemingly designed for Anita’s opaque voice) to “To Keep My Love Alive” (a catalogue song compiled for Vivienne Segal, the murmurously murderous Morgan Le Fay in theTwain reconstruction of the Arthurian legend. Anita here, in her own version of jazz Sprachstimme, recapitulates the problems of being ” never the bridesmaid . . . alwaysthe bride.”) “Have You MetMiss Jones?'” had been strictly a man’s song, until Ella Fitzgerald created Sir Jones”‘ and doubled the song’s possibilities; Anita zips through the number with great speed, and even scats a chorus before a final reprise. In different style is “Little Girl Blue,” potentially the most lachrymose of Rodgers and Hart; Billy May has slightly accelerated its tempo, and Anita has made it a self-cynical, Dorothy Parker lament. For admirers of Rodgers’ waltzes there are two on the set: “Lover”and “Falling in Love with Love,” both newly sped up and wound into a melange of tempos. But thesession concludes on a steady, sweeter note: “Spring Is Here- comes through lushly, directly, andin quietude. It’s a fine finis, insistently making one glad that not only spring is here but also Anita O’Day and Billy May and this tribute to Rodgers and Hart.

-LAWRENCE D. STEWART